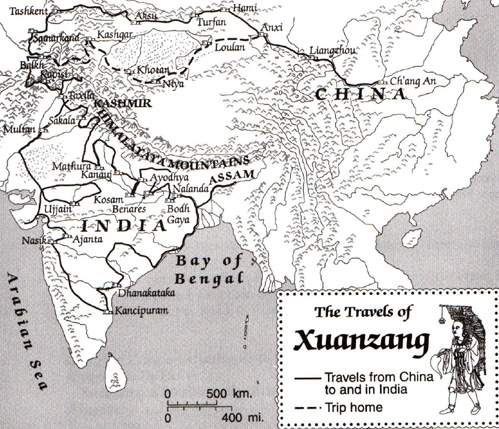

Hsuan-tsang traveled between AD 627-643. His detailed account provides the first reliable information about distant countries, terrain and customs. He traveled over land, along the Silk Road west toward India. However, the further west he traveled it became increasingly difficult to cross desert and mountain ranges. Of the Taklamaken desert he reports: "As I approached China's extreme outpost at the edge of the Desert of Lop, I was caught by the Chinese army. Not having a travel permit, they wanted to send me to Tun-huang to stay at the monastery there. However, I answered 'If you insist on detaining me I will allow you to take my life, but I will not take a single step backwards in the direction of China'."

The officer himself a Buddhist, let him pass. In order to avoid the next

outpost, he left the main foot-track and made a detour, which brought him

to a place 'so wild that no vestige of life coult be found there. There is

neither bird, nor four-legged beasts, neither water nor pasture'. At the

point of final exhaustion his only companion, his horse, turned of in

another direction, following its animal instinct, and led him to a place

where there was water and pasture. His life was saved.

Few days later he arrived at Turfan, where he stayed for some time. The

king of Turfan enchanted by the monk's knowledge of the sacred Buddha

books, refused to let him leave, only reluctantly relenting when

Hsuan-tsang threatened a hunger strike. Thus, Hsuan-tsang had peaceable

conquered to royal will. The king gave him letters of introduction the

rulers of the oases along the way,

thereby providing the assistance that made his pilgrimage successful.

The officer himself a Buddhist, let him pass. In order to avoid the next

outpost, he left the main foot-track and made a detour, which brought him

to a place 'so wild that no vestige of life coult be found there. There is

neither bird, nor four-legged beasts, neither water nor pasture'. At the

point of final exhaustion his only companion, his horse, turned of in

another direction, following its animal instinct, and led him to a place

where there was water and pasture. His life was saved.

Few days later he arrived at Turfan, where he stayed for some time. The

king of Turfan enchanted by the monk's knowledge of the sacred Buddha

books, refused to let him leave, only reluctantly relenting when

Hsuan-tsang threatened a hunger strike. Thus, Hsuan-tsang had peaceable

conquered to royal will. The king gave him letters of introduction the

rulers of the oases along the way,

thereby providing the assistance that made his pilgrimage successful.

Traveling through Samarkand (today's Tukestan) he describes that "...this great imperial city is surrounded by a wall, about seven miles in circumference, which governs a powerful state. This is a rich land, where the treasures of distant countries accumulate, where there are powerful horses and skilled artisans, and the climate is most pleasant."

Fifteen years later Hsuan-tsang reappeared on the northern side of the Great Mountains again, but this time with his face turned toward China. He was aware of the dangers between Khotan and Tun-huang---the Taklamakan desert. He comments: "...a desert of drifting sand without water of vegetation, burring hot and the hound of poisonous fiends and imps. There is no road, and travelers in coming and going have only to look for the deserted bones of man and beast as there guide". Hsuan-tsang crossed the dread waste of desert safely, reaching Tun-huang and deposited his precious manuscripts in the monastic library at the caves of the Thousand Buddhas.

(Return of Xuanzang with the Buddhist Scriptures, Silk scroll

at Dunhuang)

His detailed travel accounts from the Silk Roads provides reliable

information about distant countries whose terrain and customs had been

known, at that time, in only the sketchiest

way. In later centuries he was immortalized as a saint and his journey

popularized in fables and vernacular literature. However, for the historian

and explorer he contributed a precise and colorful account of the many

countries along the Silk Road.

Note: During the Sui (589-618) and the Tang (618-906) dynasties, the Chinese Buddhist schools were sophisticated, and the monasteries were numerous, rich and powerful.