The International Dunhuang Project: Chinese Central Asia Online

Susan Whitfield

British Library, London

Fig. 1. The northern section of the Mogao Caves at Dunhuang.

Photo © Daniel C. Waugh 1998.

espite the excellent work of scholars over the past century, the archaeological legacy of the Chinese Silk Road has barely been explored. There is so much material, with more being discovered all the time, and it covers so many subjects, languages, religions, cultures and geographical areas, that decades will elapse before all its secrets are uncovered. The International Dunhuang Project (IDP) is now facilitating access to and study of this dispersed material by making it freely available on multi-lingual websites. IDP hopes that by encouraging and promoting international collaborations the importance of this wonderful archaeological legacy will finally be fully appreciated worldwide. The Silk Road is part of all our histories. IDP is bringing it online for everyone.

IDP re-launched its web site ( http://idp.bl.uk ) in December 2005 offering more powerful fulltext search facilities, greater functionality, educational project pages and the personalised “My IDP” project space. The IDP’s web site is now hosted by sites worldwide and in English, Chinese, Russian, Japanese and German versions. After just ten years, IDP already holds information and images of over 50,000 paintings, artefacts, manuscripts, textiles and historical photographs from Dunhuang and other sites in Chinese Central Asia. By 2010 over 80% of the material from Dunhuang and a large part of the material from other archaeological sites will be available, with over 200,000 images, scores of catalogues, translations, educational pages, photographs, maps and research. Chinese Central Asia will be online.

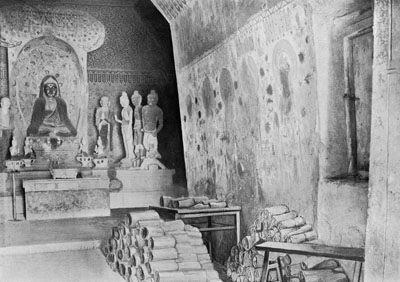

Fig. 2. Aurel Stein’s 1907 view of Mogao Cave 16, with a portion

of the manuscripts from Cave 17 (on right). Photograph © The British

Library, Stein Photograph Serindia Fig. 200, used with permission.

All rights reserved.

Background

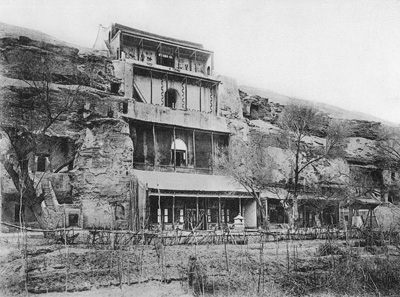

As Buddhism spread along the Silk Road from India into China at the beginning of the first millennium, monks and merchants adopted the Indian practice of paying for cave temples to be dug out from cliffs as an act of merit. These caves were then painted from floor to ceiling with scenes from Buddha’s life and depictions from the sutras, and further adorned with statue groupings showing Buddha with his disciples and guardians kings. The Mogao cave complex at Dunhuang was begun in CE 366, and by the ninth century there were over 500 cave temples with many residential caves for the scores of artisans, painters and sculptors working there [Figs. 1, 6].

Dunhuang was one among many such Silk Road cave temple sites but is unique because of the discovery in 1900 of a library cave which had been sealed and hidden in about CE 1000 [Fig. 2]. Containing tens of thousands of manuscripts and the earliest dated printed book, this is the world’s earliest and largest paper archive [Fig. 3; for other images of some of these treasures, see the articles by Connie Chin and Jonathan Bloom]. It also contained hundreds of fine paintings on silk, hemp and paper. Numerous other ancient Silk Road sites in Chinese Central Asia yielded other important artefacts, paintings, textiles, coins and manuscripts in over twenty languages and scripts, and this and the Dunhuang material was dispersed to institutions worldwide, making access difficult. The amount of material, its age, fragility and uniqueness also created a problem for conservators. Throughout the twentieth century much remained in need of conservation and therefore also uncatalogued, unpublished and inaccessible.

The International Dunhuang Project — the First Ten Years

The International Dunhuang Project (IDP), with its directorate at the British Library, was founded in 1994 to address these problems by creating a partnership of all the major holders of the material to work together on conservation and cataloguing and to increase access. To achieve the first, IDP organises regular conservation conferences and has a publications programme to disseminate conservation, scientific and scholarly information (for details see IDP News 24, available free from IDP or online at http://idp.bl.uk/pages/archives_newsletter.a4d ). To facilitate access IDP decided to create a comprehensive online catalogue of all the material, linked to high-quality digital images and supporting information which would be made freely available to all. Starting with a grant from the Chiang Ching-Kuo Foundation and a staff of one, the first few years of IDP were spent designing and implementing a cataloguing and image m a n a g e m e n t database. A British Academy-funded research assistant started adding information about the British Library manuscripts in 1995. In 1997 with a further grant from the Heritage Lottery Memorial Fund, IDP expanded and employed staff to start work on the cataloguing and digitisation of Chinese, Tangut and Tibetan materials from various Silk Road sites, and in October 1998 the web site went online with details of over 20,000 manuscripts.

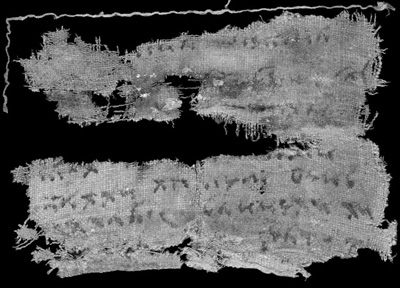

Fig. 3. Detail of the outer “envelope” of Ancient Sogdian Letter No.

2

(BL Or. 8212/99.1), discovered by Aurel Stein in 1907 at Watchtower

T.XII.a on the Dunhuang Limes. Photograph © The British Library,

used with permission. All rights reserved.

Other projects followed. A grant from the Higher Education Funding Council for England led to the launch of a map interface to the database in 2000. In 2001, a four-year grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation enabled IDP to establish a digitisation studio with the latest large-format digitisation equipment. Two conservators, three photographers and three Photoshop® operators were employed to work full-time on the Dunhuang material.

Collaboration started with the National Library of China (NLC) in the same year, funded by the Sino- British Fellowship Trust, and the skills learned in London were passed on to the IDP photographers in Beijing. The Chineselanguage version of the web site and online database were launched on a local server in November 2002 ( http://idp.nlc.gov.cn ). Institutions such as the NLC are founding members and full IDP partners. Local staff at the IDP Centre in Beijing add information about their collections into their local database and local photographers digitise the collections, using mutually agreed IDP standards and procedures (published online). Data are synchronised between the Chinese and English servers. The NLC images, apart from the reference thumbnails, are also kept on the NLC server.

IDP acts as a host for some institutions’ collections. For example, the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin and the Freer Gallery in Washington DC both have three items from Dunhuang. They supplied IDP with largeformat photographs of these, which IDP then scanned and added to its web site with cataloguing details. IDP also hosts images of the paintings from Dunhuang held in the British Museum and is just starting to add images of the textiles from the Chinese Silk Road in the Victoria and Albert Museum and other artefacts from the British Museum. In all cases the holding institution retains copyright on the images and there is a clear link on the IDP site to the institutions’ own websites. Information on the participating institutions and their collections is on the advanced search page.

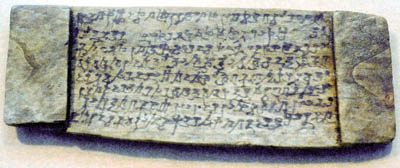

Fig. 4. Administrative document in Kharosthi script, found at Niya

by

Aurel Stein. National Museum, New Delhi.

Photograph © Daniel C. Waugh 2001.

Other collaborations launched during the past two years involve the Institute of Oriental Studies in St. Petersburg, Ryukoku University in Kyoto, and the Staatsbibliothek and Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities in Berlin. The online Russian, Japanese and German versions of the IDP site are hosted by these institutions. IDP hopes to start similar collaborations with the Dunhuang Academy, the National Museum, New Delhi [Fig. 4], the Museum for Indian Art, Berlin [Fig. 5], the Musée Guimet and the Bibliothčque nationale de France. At present, over 20,000 highquality images are being added annually to the database, but this figure will be doubled if funds can be secured to upgrade equipment and expand existing staffing in the UK, China and Germany. IDP will add more institutions and include in its database small and private collections throughout the world.

Systematic cataloguing of this material is essential if it is to be a useful scholarly and educational resource. The Chinese Section at the British Library has been collaborating with Chinese scholars for three decades to make material more accessible. As a result, the previously unconserved and uncatalogued fragments from Dunhuang (Or.8210/S.6981 onwards) were all conserved in the 1980s and cataloguing taken on by Professors Rong Xinjiang (non-Buddhist material) and Fang Guangchang (Buddhist fragments). The first catalogue was completed in 1999 and Professor Fang’s is nearing completion. Professor Sha Zhi has also recently completed his catalogue of Chinese fragments. Dr. Jake Dalton and Dr. Sam van Schaik’s catalogue of the Tibetan tantric material is now online and will be published next year, Professor Tsuguhito Takeuchi has catalogued other non-Buddhist Tibetan material, and Professor Oktor Skjaervř has catalogued the Khotanese fragments. Work is now starting on the Sanskrit material. These are just some of the major projects on the British Library manuscripts. S i m i l a r endeavours are underway on all the collections.

Fig. 5. Leaf from a 8th-9th-century Manichaean book. Qocho,

Temple K. Museum für Indische Kunst, Staatliche Museen

Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin, MIK III 6368.

Photograph © Daniel C. Waugh 2004.

All these s c h o l a r s have agreed that their catalogues be available online, and the relaunched IDP website enables users to browse a catalogue and carry out full-text searches. It is important to apply internationallyaccepted metadata to the online catalogues, and more will come online during 2006 as IDP staff complete this (the catalogues are prepared as XML documents). The catalogues offered will include “legacy” catalogues — those published from as early as the beginning of the twentieth century. Although some of the scholarship in these might now be superseded, they all contain much useful information and are an essential resource for any scholar. So, for example, by the middle of 2006 Stein’s original entries on the Dunhuang paintings will be accessible alongside Fred Andrews’ 1933 catalogue and Professor Roderick Whitfield’s detailed 1982-1985 Kodansha publication. Moreover, any scholar working on items in the database is welcome to submit his/her research for online publication, and an XML template and instructions are available.

Apart from the continuing digitisation of Dunhuang Chinese materials in collections worldwide, work has been completed on the Tibetan woodslips from Miran and elsewhere, Chinese Handynasty wood shavings from the Dunhuang limes, Tocharian tablets, and Kharosthi material from Niya and Loulan in the British Library collections. IDP has also started digitising Sanskrit, Khotanese and Tangut manuscripts and continues digitisation of the thousands of historical photographs and maps of the Silk Road and its sites made by Aurel Stein and others. IDP has achieved far more than it could possibly have expected when founded a decade ago, but the collections are so rich that much remains to be done.

In addition to conservation and digitisation, IDP continues with scholarly work. In 2005 it completed a three-year collaborative research project to catalogue and digitise the Tibetan tantric manuscripts from Dunhuang. Carried out in conjunction with the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London and funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, this project by Dalton and van Schaik uncovered many surprising results, including the possibility that most of these manuscripts were transcribed in the latter half of the tenth century by a small group of scribes. The manuscripts were previously generally assumed to date from the period of the Tibetan occupation of Dunhuang, from the mid-eighth to mid-ninth centuries. These results will form the basis of the just-started palaeographical research programme (see below).

Educational Outreach in the Years Ahead

Now the infrastructure and a significant body of material has been established, IDP is planning to reach out into the wider community by creating web-based educational resources — in local languages and with local teachers — and not only for higher education but also for schoolchildren from Shanghai to Sacramento. One of the first IDP educational resources to go online was a history of Chinese bookbinding, illustrated by Silk Road manuscripts and written and designed by Colin Chinnery. This continues to prove one of the most visited pages of the web site. Web pages on Dash, Stein’s canine travelling companions, and on Buddhism in Central Asia, have been added in the past few years and also proved popular. The second of these has now been adapted by Sam van Schaik following his teaching of the subject at the School of Oriental and African Studies and will form the opening project on the “My IDP” personalised web space in early 2006. Educational outreach projects will be started with the Dunhuang Academy and the National Library of China for Chinese schoolchildren.

Gansu Basic Educational Project (GBEP; http://www.gbep.org/en/about.asp ) to produce a bilingual booklet and DVD containing text, images, music, and video telling the story of Dunhuang. This is now being distributed to primary-school teachers in the poorest townships of Gansu and will give schoolchildren an opportunity to learn about their local history. This DVD uses some of the resources prepared by 12-18 year-olds as part of the 2004 Silk Road exhibition educational project. Next year IDP will collaborate with a European Union-funded project for children in schools throughout the EU. Also coming online in early 2006 will be the “Silk Road Quest,” a web adventure for older children devised by Gizella Dewath.

In doing such projects IDP hopes to bring a greater awareness of this rich cultural legacy to the people of the region and others worldwide. The web database will be made even more accessible through the addition of the personalised web space, an interactive map interface, photographs, music, video clips and translations. We are looking to make new partnerships with organisations and institutions with expertise and presence in the region to maximise access and understanding of this material.

Fig. 6. Façade of Mogao Caves, including Cave 96, photographed in

1908 by

Charles Nouette. Source: Mission Pelliot en Asie Centrale.

Les Grottes de Touen-Houang

(Paris: Geuthner, 1914; facsimile ed. 1997).

Cataloguing will continue, and during the period 2006-2008 IDP will also work with scholars and universities worldwide to create a new field of palaeographical studies for East Asian manuscripts. This will include a database of millions of Chinese characters and tens of thousands of Tibetan syllables digitally “cut out” from the manuscript images, along with full details about the physical aspects of the manuscripts, including laid and chain lines, type, colour and size of papers. The dataset will be freely available and be used by IDP used to test hypotheses about the date and provenance of the manuscripts. The tools prepared on this project, such as the cutting-out software, will also be freely available for others scholars to use.

Funding

From its inception, IDP has been an externally-funded project. The generosity of our supporters has enabled IDP to accomplish all that has been achieved to date, and we would like to take this opportunity to say again how grateful we are for this. We are particularly delighted by the number of donors who have renewed their grants or made additional gifts.

In 2005 three major grants came to an end, and IDP has been actively fundraising to enable it to achieve its programme for the next five years. It has grants promised from the Leverhulme Trust (for the palaeographical project), the Ford Foundation (for promoting scholarly interaction between India, China and Russia), the Pidem Fund (for general IDP work) and from several other foundations for smaller amounts. In addition to grants from organisations, individual donations remain a vital element of IDP’s funding (for a list see http://idp.bl.uk/pages/supporterslist.html ). For example, these donations have given us the flexibility to enhance the catalogue in response to new technologies and requests from our users — as illustrated by “My IDP,” the personalised IDP web space. Similarly, “Sponsor a Sutra” ( http://idp.bl.uk/forms/sponsorSutraChoice.a4d ) donations have enabled us to conserve and digitise a number of unique and fragile manuscripts, ensuring they can be accessed by scholars and the wider public now and in the future.

IDP now has a skilled and committed staff working worldwide and is within sight of its primary objective of finally making the Dunhuang and other Silk Road manuscripts, paintings, textiles and artefacts readily available to all. However, IDP urgently needs to secure further funding to realise this. IDP can celebrate its achievements of its first ten years. It is hoped that funds are soon forthcoming to ensure that the full potential of these is realised over the next five.

About the Author

Susan Whitfield is Director of the IDP and author of several books, including Life along the Silk Road (1999), Aurel Stein on the Silk Road (2004) and a forthcoming Historical Dictionary of Exploration of the Silk Road. She edited the catalogue for the British Library’s Silk Road exhibition which she helped organize in 2004, The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith, a volume which contains a number of stimulating essays presenting the results of new research in the material IDP is making accessible.

References

- Fred H. Andrews. Catalogue of wall-paintings from ancient shrines in Central Asia and Sistan recovered by Sir Aurel Stein. Delhi, 1933.

- Jacob Dalton and Sam van Schaik. Catalogue of the Tibetan Tantric Manuscripts from Dunhuang in the Stein Collection. First electronic edition. [London:] IDP, 2005, online at http://idp.bl.uk/database/oo_cat.a4d?shortref=Dalton_vanSchaik_2005 . Fang Guangchang. Ying guo tu shu guan cang dun hang yi shu mu lu. (S.6981-S.8400) (Catalogue of Buddhist manuscripts in the Dunhuang collection of the British Library not included in Lionel Giles’ catalogue. First volume [Or.8210/ S.6981-8400]). Beijing: Zongjiao wenhua chubanshe, 2000.

- Rong Xinjiang. Yingguo Tushuguan cang Dunhuang Hanwen fei fojiao wenxian canjuan mulu (S.6981-13624) (Catalogue of the Chinese Non-Buddhist Fragments [S.6981- 13624] from Dunhuang in the British Library). Hong Kong Studies Center for Dunhuang and Turfan: 4. Taipei: Shin Wen Feng Print Co., 1995.

- Prods Oktor Skjaervř, with contributions by Ursula Sims-Williams. Khotanese manuscripts from Chinese Turkestanin the British Library: a complete catalogue with texts and translations. London: The British Library, 2002. M. Aurel Stein. Serindia: Detailed report of explorations in Central Asia and westernmost China carried out and described under the orders of H.M. Indian government by Aurel Stein. 5 vols. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1921.

- Tsugohito Takeuchi. Old Tibetan Manuscripts from East Turkestan in the Stein Collection of the British Library. 3 vols. The Centre for East Asian Cultural Studies for Unesco, The Toyo Bunko & The British Library Board, 1997-.

- Roderick Whitfield. The Art of Central Asia: the Stein Collection in the British Museum. 3 vols. Tokyo: Kodansha, 1982-1985.

Details of IDP’s funding appeal can be found on http://idp.bl.uk/ pages/about_funding.a4d. All donations are greatly appreciated and put directly to the work of IDP. It is possible to make a donation to cover a specific area of IDP’s work, such as sponsoring a digitisation team, sponsoring a new camera for China, or sponsoring conservation and digitisation of a specific group of items, such as Khotanese manuscripts, textiles, Chinese sutras, Kizil murals, Tibetan pothi or Tangut fragments. Please contact Susan Whitfield at the address below if you would like to discuss these or other areas of sponsorship. We need your support.

IDP, The British Library,

96 Euston Road,

London NW1 2DB, UK

tel: +44 (0)20 7412 7319,

fax: +44 (0)20 7412 7858,

email: idp@bl.uk

http://idp.bl.uk