Kyrgyz Healing Practices: Some Field Notes

Jipar Duyshembiyeva

University of Washington, Seattle

© 2005 Jipar Duyshembiyeva

yrgyz traditional healing practices display a mixture of Islamic and pre-Islamic practices of the Turkic peoples. Like many of the other peoples of Central Asia, before the spread of Islam Kyrgyz worshipped spirits of their ancestors, different animals, mountains, trees, running water, and fire. Along with Islam, especially in its Sufi forms, some of the traces of this ancient practice still can be found in daily lives of the Kyrgyz. Most of the healers today associate their healing power with Islam; however, the healing practice itself and tools they use clearly show its strong connection with pre-Islamic values and practices. What follows is primarily a descriptive presentation of field work observations from the summer of 2001. Contextualization with a closer examination of the scholarly literature is a project for the future.

The main figure in many of the traditional ritual practices is the shaman. The word “shaman” itself is a Tungus word, and only the Tungus called their shaman by the name “shaman” among all the “shamanist” peoples of the world [Arik 1999, p. 368]. Among Kyrgyz, shamans are called baqshï, a word whose exact meaning is disputed. Some sources say that the word derives from Sanskrit bikshu, which means “Buddhist monk, shaman, or healer” [Bartol’d 1963, p. 454]. Other scholars insist on a Turkic origin of the word. They argue that it came from the Turkish word baqmak which means “to look after, to take care” [Shaniiazov 1974, p. 327]. Whatever its derivation, among the Kyrgyz the word refers to a person who is believed to possess the power to heal, to find lost or stolen things and foretell the future.1 Together with the word baqshï, Kyrgyz use such terms as tabïp (from Arabic, “healer”) and közü achïk (lit. “the one with opened eyes”). The latter term generally refers to people who are mostly engaged with finding lost objects or people and fortune-telling. However, they also practice healing.

The role of shamans in Central Asia was especially important before the spread of Islam. They occupied a special place in society, since people considered that they had the ability to communicate with spirits of their dead ancestors. Many shamans were also spiritual leaders of their tribes. Every tribal leader would seek the shaman’s blessing before going to war against another tribe. Healing, however, remained the most important part of shaman’s activities.

Several sources describe shamanic practices and shamans among the Kyrgyz before the end of the nineteenth century. Two of the major ones are the accounts by Wilhelm Radloff and Chokan Valikhanov, who traveled to the region to conduct broad research on nomadic people of Central Asia and wrote at length about the shamanic rituals and the role of shamans among the Kyrgyz and Kazakhs. Valikhanov notably tended to downplay the Islamic elements which were already prominent in Central Asian Turkic “shamanism” [Privratsky 2001, p. 11]. Perhaps the best modern study of shamanism, which underscores the idea that it is not a “religion” per se, is Caroline Humphrey’s book using the example of the Daur Mongols. Additional material may be found in work by Vladimir Basilov, Bruce Privratsky, and Kagan Arik. A monograph in French by Patrick Garrone deals specifically with the institution of the baqshï and is based both on written sources and extensive field work, especially among the Kazakhs.

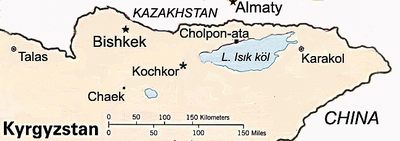

I undertook my field work in the summer of 2001 as part of my University of Washington M.A. program. The goal was to observe some of the shamanic practices that are alive today and to interview practicing baqshïs. The observations were made in the region of Kochkor, a small town in northern Kyrgyzstan. My mother is from a nearby village, Komsomol, where I lived until age of five and have visited every year since; my grandmother and my late grandfather also lived in that village. It is there that I made the acquaintance of the healer Kalïi, [Fig. 1, next page] famous not only in Komsomol, but also in most of the surrounding region. People even come from the capital, Bishkek, to be healed by her.

When we arrived to Kalïi apa’s2 house, she was seeing a toddler. His mother had brought him to Kalïi apa, because he had not slept for several nights in a row and had been constantly crying. Kalïi apa had painted the child’s face with a paint used for coloring felt rugs. She told me that the bright colors would lure the evil spirits out of the child’s body; they would lick the paint and leave the boy alone. This belief also exists among other Central Asian people. However, healers may use different tools in order to achieve the same goal.3 Further, Kalïi apa filled a cup with some ashes and covered it with a piece of cloth. Then she touched the body of the child from head to toe with the cup turned upside down. After she was done, Kalïi apa uncovered the cup, which was now only half full. She poured the remaining ashes onto the toddler’s jacket and left it next to the wood stove where it was supposed to lie for seven days. The boy, who had been crying constantly before the healing, seemed to quiet down now. When Kalïi apa handed him over to his mother, I started my conversation with her.

Fig. 1. Kalïi apa treating a patient. Photograph © Jipar Dushembiyeva 2001.

Kalïi apa remembers that she began to heal people at the age of twenty-seven when she came to her husband’s village. She would often get sick for no apparent reason and would not know what to do about it. She consulted many healers, but nothing helped. She refused to take up the healing profession for as long as possible, but finally she had to give in.4 She started with one of the easiest practices that can in fact be done by almost anyone, lifting children’s hearts, that is, comforting them when they had experienced a serious fright. She then began to visit mazars (shrines), making sacrifices and staying there overnight and praying. Although she could not explain to me the source of her power or the way in which it operates, she repeatedly emphasized that it helps her to heal people and she follows its directions.

Kalïi apa states that she can heal liver diseases, help those who have arthritis, and relieve severe lower back pain by drawing blood. She also takes the pulse [lit.”takes vein”5]; that is, by touching the artery she can tell what the person’s sickness is and the ways she can help him/her. If, after taking the pulse, she knows that the person is incurable,6 she never tries to heal him/her. In that case Kalïi apa admits her inability to cure and she advises the patient to find some other healer or see a doctor. However, if she is sure that she can heal the person, she does everything in her power to help. Kalïi apa also told us that she has “bio-energy” and uses it in her healing.

Another story told by Kalïi apa is quite interesting. A friend of hers in the village had cancer. She called in Kalïi apa one day, asking that she take her pulse in order to find out how long she would live. But Kalïi apa refused to do so and left. Next morning she asked my grandmother to come with her and see her friend, but it turned out that the latter had died the previous night after Kalïi apa left. She says that merely by looking at her friend she knew that “her days were numbered” (köröör künü az kaldï).

Kalïi apa also claims that she has the ability to find lost or stolen things and has the ability to foretell the future with the help of fortyone stones.7 When telling fortunes, she never tries to make a person avoid a certain event. She insists that everything is controlled by God, and there is no way to avoid one’s own fate. However, since she advises people how to act in a certain situation, they come to her with their various daily problems. She relates an incident in the 1970s in the same village which almost persuaded her to give up fortune telling. My grandmother and Kalïi apa are very close friends, and their houses are situated not far from each other. The son of their close neighbor went to serve in the army. While they were waiting for his return, with the help of the stones, my grandma and Kalïi apa tried to predict the exact time of his arrival. When spread out, the stones would always show a coffin, a prediction which they did not dare tell the boy’s mother. Yet he returned home safe and sound to much rejoicing, only to die two months later. After that my grandmother swore never to touch the stones again. For a time Kalïi apa refused to tell fortunes, but finally she again gave in to those asked for her help.

In addition to her pulse taking, predicting the future, and healing little children using traditional ways, Kalïi apa also draws blood. My grandmother still remembers how it all started. Kalïi apa came to their village in 1964 when still very young, some twenty-two or twenty-three years old. Nobody knew that she had the ability to heal illnesses or relive somebody’s pain. When children took ill, people would not know what to do. To visit to a good doctor was costly and the distance too far; so people looked for more immediate help. There were some elderly people in the village who could help, but not much. Whenever Kalïi apa came to visit my grandmother’s house and would touch a sick child’s head the child would feel better. As her reputation for healing grew, people started taking their ill children to Kalïi apa. From just touching a person she slowly switched to healing with the help of the ashes, knives, paper, etc.

My grandmother remembers that at that time she started having constant headaches. She tried taking some pills but developed allergies to them which caused her face to swell. Her visit to a doctor in Karakol (a town at the east end of Lake Ïsïk Köl) did not help. On the way home, she thought of asking Kalïi apa to draw her blood. Kalïi apa, who had never performed the procedure before, was terrified and refused my grandmother’s request. She said that she had seen her grandfather do it but was afraid to try herself. Finally she gave in. My grandmother shaved a small area on her head, and Kalïi apa made several cuts on her head through which the “bad blood” came out. My grandmother says that since then her head never was cold, and the constant headaches stopped.

Nowadays, due to my grandmother’s advanced age, Kalïi apa does not make cuts on her head. Instead, twice a year, Kalïi apa makes small cuts on her back. Another thing that my grandmother remembered was that a while ago doctors told Kalïi apa’s daughter she had a high blood pressure and wanted to put her in a hospital. Unwilling to trust the doctors, Kalïi apa said she would cure her daughter herself; she combined all the leeches8 that my grandmother and she herself had and put all of them on her daughter’s back. According to my grandmother, “they sucked off all the blood that was causing pain.” The next day the girl went to the hospital where doctors found out that she did not have any high blood pressure and was fine. When the daughter started having constant headaches, medicine did not help. Again her mother convinced her to have her blood drawn, which relieved the pain. Since then, she said, she comes twice a year to get rid of her “spoiled blood.”

I witnessed the blood drawing on one of these visits. The procedure involved the use of glasses, buttons, a piece of cloth, matches, a little bucket, and a razor. Having prepared everything Kalïi apa took a blade and made three one-inch cuts on both sides of her daughter’s back. Then she wrapped the buttons in two small pieces of cloth, placed them close to the cuts, and lit them with the matches. After that she quickly put glasses on top of the flaming buttons. Once the buttons were covered, blood started coming out of incisions.9 After 1-3 minutes she took the glasses off and wiped the blood from her back. She repeated this procedure several times making cuts in different places. After a considerable amount of blood had been drawn, she stopped the procedure and wiped her back with a piece of cloth soaked in alcohol.

It is not easy to watch the procedure of blood drawing especially if seeing it for the first time. Furthermore, for a person used to ideas about the importance of a sterile environment, the procedure would be disturbing. The tools she was using were very basic, the piece of cloth she used for wiping the cuts was quite dirty; she did not seem to bother about the cleanliness of her tools and disinfecting them and her daughter’s back before making any cuts on it. Only at the end of the whole procedure did she use some alcohol to wipe her daughter’s back with the cloth soaked in it.

Blood drawing was the last procedure that Kalïi apa performed that day. Towards the end she felt quite tired and looked exhausted. She explained to me that during the procedure she thinks about the patient’s illness and takes it onto herself. She mentioned that sometimes she gets sick for a while herself, because she gives all her energy to the patient. She does not take anything for her services; “I take only whatever my patients bring me, what comes from their hearts. I never ask for anything specifically, I don’t ask for money, and if they brought anything, they leave it on the table,” she said. Later, I found out that she is the sole supporter of her family. Her youngest son and his wife and children stay with her, but there is no job in the village for them. They keep a small number of sheep and have some cattle. People who visit her bring tea, bread, candies or cookies; some of them leave money.

I next visited the Kochkor Ata shrine located in the northwestern part of Kum Döbö village. It is called a mazar, or a shrine, a term used to refer to graves of venerated Muslim saints. The activities at the shrine pointed clearly to the fusion of Islamic belief and practice on the one hand and traditional, non-Islamic practice on the other.

The shrine consists of two low hills which are joined and people say resemble from a distance a resting camel. It is visited by many people, often from distant parts of Kyrgyzstan. Some come every Thursday to pray for their deceased relatives, others come to make a sacrifice in their ancestors’ honor; a third group comes to find some cure for their illnesses. One can also meet married couples who cannot have children and for whom this is their only place of hope. Another significant group of visitors are baqshï. Experienced ones bring their patients, because it is a general belief that there is a greater chance of a cure if the performance is conducted at the holy places where the spirit of the ancestors is strongest. Younger baqshï come to Kochkor Ata shrine for the initiation ceremony, usually accompanied by more experienced ones, and they spend a night there.

There is a small three-room building next to the shrine. People who bring food or slaughter a sheep for sacrifice use the building as a place to gather other pilgrims, share their food and recite the Quran at the end of the ceremony. A local mullah (Muslim religious authority) maintains the place and makes it his task to take people around the shrine. The major part of the ceremony consists of going around the hill, making some stops on the designated areas along the way and reciting the Quran. There are several caves in the mound where candles are set at nighttime.

There are many legends about Kochkor Ata and why that place became sacred. Some people say that Kochkor Ata was a Muslim saint and was buried in that place after his death. Since then, the place of his burial became a place of pilgrimage for many people. Others connect the history of Kochkor Ata shrine with Kyrgyz folklore. Thus, Kazakh ethnographer Chokan Valikhanov mentions that Kazakh sultan Barak, who lived at the end of eighteenth century, “became careless, and showing off his strength he invaded the sacred place of the Kyrgyz, Koshkar Ata.” The Kirghiz became angry, attacked Barak’s camp, and pursued his army as far as the Ili River. “The Kirghiz,” writes Valikhanov, “attributed their enemies’ escape to the holiness of Kochkor Ata” [Valikhanov 1985, p. 375]. There is another legend told by a man from Cholpon Ata, who said that Arslanbab (a mazar in Southern Kyrgyzstan) had seven children. And the seven mazars, Oisul Ata, Karakol Ata, Shïng Ata, Manzhïl Ata, Cholpon Ata, Kochkor Ata, Oluia Ata, were built in their honor [Abramzon 1975, p. 304]. It is worth noting that in the Soviet period, as part of the effort to discourage Islamic practice, the authorities undertook severe measures to prevent worship at mazars.

I went to Kochkor Ata with my family. We brought some bread, fruits and vegetables, and some sweets to the shrine. Since we went on Thursday, the local mullah was expecting a large number of people to come that day. We were the third group to enter the house near the shrine. It was full of visitors already. A group before us had slaughtered a sheep not long ago and the meat was boiling outside in a big qazan (cauldron). We were invited to join others for the meal. After we finished the meal, the mullah recited The Quran and took all of us outside the building. He led us to the hill, where we started our journey. There was a certain path one had to follow. The mullah was in front of us constantly saying La Illaha Il-Allah which means “None but Allah is worthy of worship.” He made stops on the way at several places, usually next to the big rocks, in order to recite The Quran. After the recitation people kissed the stone and touched it with their foreheads.10 The whole process took us forty-five minutes. We saw many pilgrims who were sitting down and praying during our walk, and it was quite a busy place. Finally, we reached our starting point where our mullah recited The Quran for the last time. It was there that I met my next informant, Kümüsh Zhanibek kïzï, another baqshï from the nearby village, who brought her patients to the shrine to perform her healing rituals in ways which very much resembled shamanic practices described from earlier times.

Kümüsh approached the shrine with five of her patients just when we were done with our ceremony. Their behavior was submissive, and they followed her instructions carefully. They brought some bread, watermelons, pilaf, and some vegetables to the house next to the shrine. She was leading her group towards the hill when I started a conversation with her; she allowed me to videotape her performance.

Kümüsh led them to a place surrounded by small rocks close to the hill. They knelt down, and one of the men in the group recited The Quran. After he finished, Kümüsh began her ritual. She recited The Quran, and after that she spread her palms and started saying rapidly the following:

I devote This Quran to Kochkor Ata,11 Shaban Shorobek Ata, to all the spirits surrounding Kochkor Ata, to all those who have passed away, to all children who died young, to those who were buried with their clothes, to the blind, and to the great khans.

Bissimilla Rahman Rahim, I devote my prayer to my Zhumgal Ata, Tosor Ata, Baba Ata, Ïsïk Ata, Ïsïk Köl Ata, Cholpon Ata, and to my generous Manas Ata, and his forty companions, to those holy fathers and mothers who perished between the East and the West, to the old people, to the widows and orphans, to the mother lake and father lake, to the sacred shrines surrounding the lake,12 to the masters of those shrines, to Manzhïl Ata, to his sacred supporters, to Kalïghul Ata.

[I devote my prayer] to the seven forefathers of the people who came here to visit [the shrine], to the common spirits, to all those who passed away, to all children who died, to their seven forefathers and seven foremothers.

Save from the evil eye and evil word of others your creatures who came here saying your name and asking their wishes be granted. Forgive the one mistake that they made in their lives unknowingly. Grant their dreams and wishes. May their enemies be far from them and their friends close to them. Provide a cure for the illness of these people. Open the white path to those who came asking for it. If they gave their heart to you, grant their wishes.

Oomiin, Alohu-Akbar.

Upon finishing her prayer, Kümüsh began her healing. Her patients sat down in a row facing Kochkor Ata shrine with their heads down. Kümüsh held a whip in her hands; she started walking back and forth in front of her patients while singing aloud the following song:

Kochkor Ata, please help, Allah, To a person who came saying “Allah”

Open his white road wide.

Allah oh, Allah eh…

Provide a cure for your creature Who came in illness. Give cure for [his] sickness. My first hill, double hill. Kochkor Ata, please help. My second hill, double hill. The one which a horse circled.

Allah oh, Allah eh…

I’ll call you, saying “Allah” Kochkor Ata please heal [them?].

I’ll call you, saying “Allah” Zhumgal Ata please come. Take my white wishes.

Allah oh, Allah eh…

I’ll call you, saying “Allah” Ak Mazar Ata, please come. Give them their white paths.

Allah oh, Allah eh…

Creator Allah, [sacrifice], Allah I’ll spread my white beard. Ak Mazar Ata, please come Give your help.

Allah ho, Allah eh…

Manas Ata, please help. I called you, saying “Allah.” Please, you, yourself always help.

Allah eh, Allah oh…

Creator Allah, bless Allah, Ak Mazar Ata did you come? Baba Ata, you yourself purify. Put [them] in the right path. If he sinned without knowing, Tosor Ata, please purify.

Allah eh, Allah oh…

CHUPH, CHUPH, CHUPH…

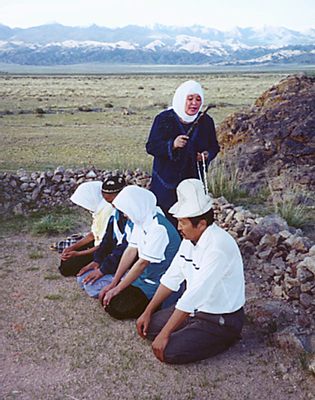

Several times during the ceremony Kümüsh hit some of her patients with the whip she was holding [Fig. 2]. After she was done with the song, she started to ‘spit’ on her patients and make circular movements with her hands above their heads as if she was lifting invisible objects from their shoulders.13 She ended her ceremony with the words, “All of you spread your palms, and invoke Kochkor Ata. Tell him the wish with which you came.” She pronounced a prayer in Arabic and said “Oomiin” [Amen].

After Kümüsh was done with the healing ceremony, I asked some questions regarding her performance. She gave me an explanation of what she had to go through to become a healer and her healing method:

Fig. 2. Kümüsh with her whip.

Photograph © Jipar Dushembiyeva 2001

After I started my healing practice, I was able to give birth to two children. Had it not been for them, I doubt whether I would have started healing. My practice is closely connected with medicine and also with religion.16 If people do not get well we send them to the doctor. We ask them to have the laboratory analyses. The first year when I started examining17 people, I did not know how to recite The Quran. After that, in my dream I was told to recite Quran, and that is how I started.

As one can see, Kümüsh also connects her healing ability to a power, but unlike Kalïi, she knows that it comes from God. She clearly states that she did not have any intention to practice healing. However, since she was not getting well from her illnesses, the only way she could be cured was to take up healing, a phenomenon typical for other practitioners. Almost all of them state that “seeing” people became a necessity for them: healing provides relief, and they start feeling better. Kümüsh was the most vocal one of all healers I met. Unlike their predecessors, modern healers prefer not to advertise their talents. In contrast, Kümüsh was very outspoken, and she was very animated, expressing her emotions during the ritual. Along with pre-Islamic rituals, Kümüsh also incorporated Quranic verses into her practice. The syncretic relationship between Islam and pre-Islamic practice was reinforced by the location of the ritual in the open air next to a shrine.

My third informant, Sarïpbek kïzï Saiasat,18 came from Talas region and now lives in Bishkek. As often seems to be the case with healers, she notes that the practice ran in the family, where her grandfathers and grandmothers were also healers even though her parents were not.19 She strongly believes that her ability to heal had been passed down to her from her grandparents. None of her eight siblings is a healer. 42 Fig. 2. Kümüsh with her whip. Photograph © Jipar Dushembiyeva 2001. Of particular interest in my interview were her observations about the relationship between Islamic and non-Islamic practice. She helps people by reciting surahs from the Quran. Kyrgyz call the practice dem sal, which, if one translates it literally, means “putting breath,” or giving to a person life by helping him breathe. When asked how she learned this practice, she responded:

She went on to explain that certain practices are definitely not Islamic; in fact her preferred instruments for healing are prayer beads.

During the conversation Saiasat also explained the purpose of each tool that she uses for healing. She uses a whip (qamchï) for very severe sicknesses, psychological sicknesses or when a person is ‘possessed’ by evil spirits. She circles the whip around her patient’s head and it brings them great relief. She uses the small whip for children and people with pain in their lower back. Sometimes it is used for the people who complain about their sleep and anxiety. Her knife is used for lifting one’s heart. She uses prayer beads for her daily prayer and for healing people as well. She also widely uses different kinds of herbs in healing stomach pain and various skin diseases.

One can find a great number of healers today in Kyrgyzstan. Their practice surfaced in more obvious ways after the country gained its independence. It is apparent that the healing tradition stayed very much alive during the Soviet regime; after all, it had existed for many centuries preceding the Soviet state. However, most of the time it was practiced in secrecy. Not many baqshï admitted their engagement with supernatural, afraid of being punished for it. The new era created many opportunities for true healers and imitators alike. People started frequenting sites like Kochkor Ata located in different parts of Kyrgyzstan; they began to take refuge in alternative medicine. This demand also helped to spawn many charlatans, who saw “healing” as a quick way to make money. It is clear though that there are many who believe sincerely in their art and their healing abilities.

During my short trip to Kyrgyzstan I was able to meet with only three practicing baqshï, only a small portion of the numerous healers in the country. Each one of them has her own unique techniques, her own tools and methods. They perceive their healing as a gift from above which they cannot resist, and each one of them has her own patients who believe in her power. It was not my goal however to decide which one of the healers possesses true healing ability and which does not, or whether they have any such ability at all. My intention was to observe a complex phenomenon that is still alive and needs further study.

About the Author

Jipar Duyshembiyeva received her M.A. from the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilization at the University of Washington in 2002. She currently works in the University of Washington libraries and plans to return to graduate school for Ph.D. work on Central Asian literature and culture. She may be reached at jipar@u.washington.edu.

References

- Abramzon 1975

Saul M. Abramzon, Kirgizy i ikh etnogeneticheskie i istorikokul’turnye sviazi [The Kyrgyz and Their Ethno-genetic, Historical, and Cultural Relations]. Leningrad: Nauka, 1975. - Arik 1999

Kagan Arik. “Shamanism, Culture and the Xinjiang Kazak: a Native Narrative of Identity.” Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation. University of Washington, 1999. - Bartol’d 1963

Vasilii V. Bartol’d. Sochineniia [Works]. Vol. 1. Moskva: Izdatel’stvo vostochnoi literatury, 1963. - Basilov 1992

Vladimir N. Basilov. Shamanstvo u narodov Srednei Azii i Kazakhstana [Shamanism Among the People of Central Asia and Kazakhstan]. Moskva: Nauka, 1992. - Basilov and Zhukovskaya 1989

Vladimir N. Basilov and Natal’ya L. Zhukovskaya. “Religious Beliefs.” In Nomads of Eurasia. Vladimir N. Basilov, ed. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 1989, pp. 160-181. - Garrone 2000

Patrick Garrone. Chamanisme et Islam en Asie Centrale. La Baksylyk hier et aujourd’hui. Paris: Editions Maisonneuve, 2000. Note: Since I do not read French I have not consulted this but list it because of its importance among modern studies of shamanism in Central Asia. - Humphrey 1996

Caroline Humphrey, with Urgune Onon. Shamans and Elders: Experience, Knowledge, and Power among the Daur Mongols. Oxford: Oxford University Press 1996. - Privratsky 2001

Bruce Privratsky. Muslim Turkistan: Kazak Religion and Collective Memory. Richmond: Curzon Press, 2001. - Radloff 1989

Wilhelm Radloff. Iz Sibiri [From Siberia]. Moskva: Nauka, 1989. - Shaniiazov 1974

Karim Shaniiazov. K etnicheskoi istorii uzbekskogo naroda: (istoriko-etnograficheskoe issledovanie na materialakh kipchakskogo komponenta) [On the Ethnic Hisotry of the Uzbek People: Historical and Ethnographic Research on the Materials of the Kypchak Component]. Tashkent: Izdatel’stvo Fan, 1974. - Sukhareva 1975

O. Sukhareva. “Perezhitki demonologii i shamanstva u ravninnykh Tadzhikov [Remnants of Demonology and Shamanism among the Valley Tajiks].” In Domusul’manskie verovaniia i obriady v Srednei Azii [Pre-Islamic Beliefs and Customs in Central Asia]. Vladimir N. Basilov, ed. Moskva: Nauka, 1975, pp. 5-93. - Valikhanov 1985

Chokan Valikhanov. Sobranie sochinenii [Collection of Works]. Almaty: Kazakh Sovet Entsiklopediasy, 1985.