TWO TRAVELERS IN YAZD

Frank Harold

Photographs by Ruth L. Harold

University of Washington, Seattle

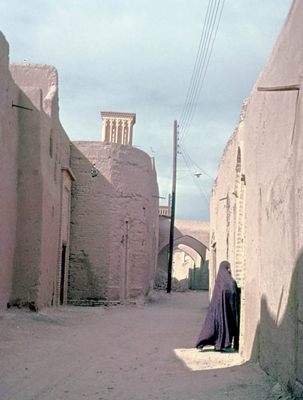

Fig. 1. Typical alley in Yazd.

Photograph © Ruth L. Harold

1970.

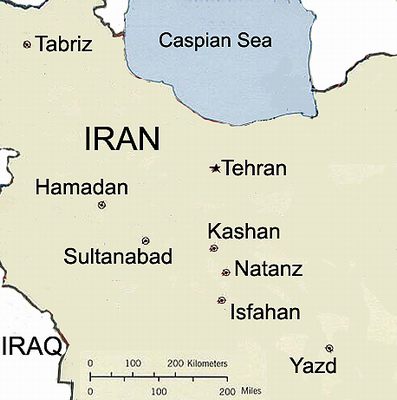

branch of the Silk Road skirts the western and southern edges of Iran’s forbidding

central desert, passing through a string of small cities — Kashan, Nain, Yazd,

Kerman — on the way to India [see map]. Of these, Yazd is the largest

and the most remarkable, a port of the desert from which tracks led to Mashad

and on to Merv, north to Rayy and south to the Persian Gulf. Always a provincial

city dependent on trade, Yazd lacks the royal monuments that lure visitors to

Isfahan and Shiraz, but camels still plod through its streets. Yazd remains

one of the few strongholds of the Zoroastrian faith, as well as a center of

Islamic art and learning. Few Iranian cities retain so well the flavor of a

civilization that has flourished for millennia in the narrow strips of irrigable

land between the mountains and the desert.

Yazd is today well off the tourist track, but as a halt on what was once the main road, earlier travelers knew it well. In the tenth century, Istakhri found it a prosperous and well-fortified town. It was spared the attentions of the Mongols, and so Marco Polo, who stopped there about 1272 CE, lauded Yazd as a “good and noble city”, noted for its fine silks. The Franciscan friar Odoric, on his way home from the Mongol court in the middle of the fourteenth century, commented on the abundance of fruit in this parched place. Tavernier, a French jeweller who wandered all over the Safavid realm in the middle of the seventeenth century, also enjoyed the fruit but reserved his highest praise for the ladies, whom he considered the most handsome in all of Persia (a contemporary visitor must wonder how he made this judgement, but the beauty of Yazd’s women was proverbial). And Robert Byron, who passed through Yazd in 1934, was bowled over by the buildings, which no one seemed to have noticed before: “Do people travel blind?” Our own account is drawn in the first place from notes on a visit in 1970, updated by a return in 2000.

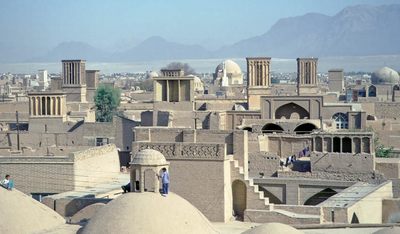

Fig. 2. The skyline of Yazd with its badgirs (ventilation towers).

Photograph © Ruth L. Harold 2000.

At first sight, Yazd is not prepossessing. Like other towns of the Persian plateau, it is a maze of narrow alleys [Fig. 1] and built wholly of mud brick. As a concession to the automobile age, the medieval fortifications were demolished and a few wide streets punched across the old city, leaving severed walls standing like survivors of an earthquake. Nevertheless, as soon as one steps off those new streets one is transported into an earlier era. The alleys wind tortuously between blank adobe walls, picturesquely bridged by arches designed to buttresss the walls against collapse. The occasional doorways, studded with great copper bosses, are always shut. They conceal courtyards and tiny gardens, but of these the passerby has never a glimpse for the Persian home turns inward, away from the street. Few houses boast more than two storeys, but all have flat roofs where great coils of dyed yarn dry in the sun and children peer down at the rare foreigner. It is startling to see a man in suit and tie emerge from one of those doorways. More in keeping with the atmosphere are the occasional women, wrapped in the all-enveloping black chador, and the men whose green turbans proclaim descent from the prophet Muhammad himself.

Fig. 3. A nakhl. Photograph

© Ruth L. Harold 1970.

The flat skyline is broken by hundreds of graceful turrets with narrow vertical slits. No, not chimneys; these are the famous badgir, windcatchers, an ancient form of air conditioning [Fig. 2, previous page]. Their purpose is to capture every breath of wind and lead it into the inner rooms, often below ground, where the family takes refuge from the fierce summer heat. Some are quite stylish, statements of individual taste that relieve the bland uniformity of adobe architecture.

Along any street one may come across a broad flight of steps descending into the ground, a hundred feet and more. At the bottom is a water tap, and this prosaic object holds the key to the very existence of a substantial city (pop. 70, 000 in 1970) surrounded by desert: the qanat. Visitors to Iran will likely first spot qanat from the air, long lines of molehills converging upon town or village. In fact, each molehill marks the opening of a shaft that leads to an aqueduct deep underground. This taps water-bearing strata at the foot of mountains that, to the casual observer, look utterly dessiccated. The tunnels slope gently and may extend for miles; some of those that supply Yazd come from the Shir Kuh range, 30 miles to the southwest. The water flows into underground storage tanks, recognizable by their mudbrick domes and badgir, and then distributed through the city. The siting, excavation and maintenance of qanat are highly specialized occupations; they are also quite hazardous, for the loose soil and gravel is forever poised to cave in. Yazdis are famous for their skills, and in demand all over Iran.

Fig. 4. An alley in the bazaar.

Photograph © Ruth L. Harold 1970.

To feel the pulse of a Persian city one must explore its bazaar. This, of course, is the shopping and business district, but it is much more than that: mosques, baths, caravanserais and schools were traditionally built right into the bazaar, making it truly the center of civic life. Conveniently, one of the most conspicuous landmarks of Yazd is the monumental gateway to the bazaar, marked by a pair of tall minarets. But once again, appearances mislead: this building, despite its name, serves chiefly as a grandstand from which to watch the processions and passion plays at Muharram, the season of deep mourning that commemorates the death of the Imam Hussein at the battle of Kerbala thirteen hundred years ago. At the foot of the gateway stands a huge wooden framework called a nakhl (one may come across several of these, tucked away in courtyards and passageways) [Fig. 3]. During Muharram the nakhl is draped with black banners and pennons, and carried through the streets on the shoulders of mourners; others chant and flay their own backs with chains in an ecstasy of grief.

Fig. 5. A baker displays his flat

bread. Photograph © Ruth

L. Harold 1970.

Yazdis have long enjoyed a reputation for industry, even hustle, and the lively bazaar is where these are on display. Like most traditional bazaars it is vaulted with brick, a welcome haven from desert dust and wind. The whitewashed corridors are cool and airy, lined with shops that offer great rolls of cotton fabric and heavy multicolored silk stuffs [Fig. 4]. In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the export of silks and carpets to India and Central Asia underpinned a period of prosperity, and these items are still celebrated. At one time Yazd was also known for decorative metalwork. That craft seems to have died out, but a search led to the street of the copper workers, adjacent to a picturesque sunny square loud with the cheerful din of metal striking metal. Here the big copper pots and trays are hammered into shape, and then passed on to a neighboring artisan who gives each vessel a final coat of shiny, non-toxic tin. The old crafts are endlessly fascinating: the smith at his forge, the furniture maker turning a lathe with his foot while his helper decorates wooden chests with red velveteen and brass nails. A candy boiler labors over a huge tray of crystallized sugar, a baker shows off flaps of fresh stonebread (sangak), surely the best bread ever! [Fig. 5, previous page.] Carding, dyeing, spinning and weaving remind one that the textile industry, which once made Yazd famous, is still very much alive.

Fig. 6. Portal of the Friday

Mosque, begun in 1325.

Photograph © Ruth L.

Harold 2000.

The lanes of the bazaar twist and turn and eventually lead to the Friday Mosque, the pride of Yazd and one of the finest in Iran [Fig. 6]. The tall façade, the shallow dome and the interior of the sanctuary hall all sparkle with glazed tile. Most of the tilework dates to the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, when the art was at its height and the city rich; no cost was spared in assembling thousands of precisely cut pieces of colored tile into large mosaics of geometric or floral design [Fig. 7]. In return for a small tip, the custodian unlocks the steps to the roof, and may even allow one to climb a minaret. In the old days, a muezzin would scale this five times a day to call his community to prayer; his modern successor understandably prefers to issue the summons from below, with the aid of records and a loudspeaker. Its a long trudge up a tight spiral staircase to the narrow balcony, where we hug the wall while admiring the view. The city sprawls below, dun-colored like the desert that gave it birth. A line of small domes traces the bazaar by which we came; here and there a larger dome, bright with blue tiles, marks a mosque or a tomb.

Fig. 7. Tilework of the Friday Mosque.

Photograph © Ruth L. Harold 2000.

Tombs of saints and martyrs are prominent in the human landscape of Iran. Many are closed to non-Muslims, but we were admitted to the Imamzadeh Jaafar, a fine example of the genre. Built in the 17th century, the shrine consists of a simple plastered chamber surmounted by a dome, its floor lined with carpets. The carved wooden cenotaph, covered with green baize, is set apart by brass railings. We could not learn who this particular Jaafar was, but his memory is still green, honored by women who come to weep and pray at the tomb while a pair of mullahs chants from the Quran. The atmosphere of Yazd is that of Islam, but the city harbors remnants of a far older order. Prior to the Arab conquest (642 CE), the dominant religion of Iran was Zoroastrianism, a faith that sees the world in terms of a contest between the principles of good and of evil. The duty of man is to take part in the moral struggle, and to hasten the triumph of the good by noble deeds, right thoughts and proper worship. The Parsees of Bombay make up the world’s largest Zoroastrian community, but active ones survive in Yazd, Kerman and Tehran. Yazd was probably a major religious center in antiquity: the Friday Mosque was erected on the site of a large fire-temple, and the very name of the city recalls that of the last Sassanian king, Yezdegird, who was driven from his throne by the Arab armies. Until quite recently Zoroastrians were regarded as idolators and subjected to various indignities: like the Jews of medieval Europe they were obliged to wear distinctive clothing, forbidden any show of prosperity, and their touch was held to pollute Muslims. They were often persecuted and denied legal redress. But Zoroastrians survived as a community and prospered in business, earning a reputation for honesty and hard work. Under the tolerant regime of the Pahlavi Shahs, their position became secure. Zoroastrians occupy a quarter in the south of Yazd. Outwardly, this does not differ much from the rest of the city, but its alleys seem more animated. That is due to the presence of women, cheerfully attired in colored shawls and baggy trousers tied at the ankles, in place of the somber black of their Muslim sisters.

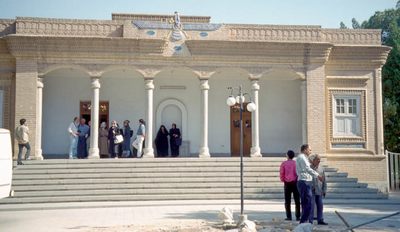

Fig. 8. The Zoroastrian temple. Photograph © Ruth L. Harold 2000.

Traditionally, Zoroastrians did not bury their dead but exposed them to the vultures in walled enclosures called towers of silence. These are outside the city, and even though the custom is fading, they are off-limits. But there was no objection to our visiting the main firetemple, a modern building of no architectural pretensions set in a shady garden [Fig. 8]. The walls are hung with oleographs, portraits of the half-legendary Zoroaster (probably sixth century BCE) and of wealthy Parsee donors. In a small room to one side stands a huge brass urn. There smolders the eternal fire, guarded by its priests and perfumed from time to time with sandalwood or aromatic herbs. This is the very focus of Zoroastrian worship. Fire represents the divine essence, the source of life, which burns in the bodies of men and beasts, in the air, even in paradise. Fire is the symbol of the ritual purity to which Zoroastrians aspire, and must never be allowed to go out. In Iran it has burned thus for some 2500 years, dimly at times but never extinguished.

Postscript

We returned to Yazd in 2000, to find that no place is immune to change. The district is now home to more than 300,000 persons, and new residential areas linked by busy roads sprawl across the desert flats. The qanat, long unequal to the demand for water, have been supplemented with deep wells. The old city, however, has been carefully protected; now designated a UNESCO world heritage site, it is considerably tidier than in was then and less picturesque, but probably more salubrious. Under the Islamic Republic dusty alleys have been paved, crumbling shrines restored and the tilework of the Friday Mosque made splendid. The view from the roof is still magnificent, though you may have to put up with the loudspeaker blaring devotional music. The Zoroastrian community, some 12,000 strong, holds its temple and its place in the city. The towers of silence are disused now, and you may look upon them from the foot. The great disappointment, here and elsewhere in Iran, was what has befallen the bazaar. The vaulted halls remain, but the workshops and their craftsmen are gone; in their place, indifferent shops sell cheap imports and mass-produced housewares. Much has been swept away, yet much remains: we cannot think of any other city that preserves so much of the atmosphere of a caravan depot on the Silk Road.

About the Author

Frank and Ruth Harold are scientists by profession and travelers by avocation. Frank was born in Germany, grew up in the Middle East and studied at the City College, New York, and the University of California at Berkeley. He is Professor Emeritus of biochemistry at Colorado State University and a member of the volunteer faculty at the University of Washington. Ruth is a microbiologist, now retired, and an aspiring painter. The Harold family lived in Iran in 1969-1970, while Frank served as Fulbright lecturer at the University of Tehran. This experience kindled a passion for Asian travel which has since taken them to Afghanistan and back to Iran, into the Himalayas, up and down the Indian subcontinent and along the Silk Road between China and Turkey. They make their home in Edmonds, Washington, and may be reached at frankharold@earthlink.net.

Sources

Earlier travelers to Yazd are cited in Guy Le Strange, The Lands of the Eastern Caliphate; Mesopotamia, Persia, and Central Asia, from the Moslem Conquest to the Time of Timur (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1905; reprint, Lahore: al-Biruni, 1977), and in Laurence Lockhart, Persian Cities (London: Luzac, 1960). For a detailed account of the history see A.K.S. Lambton, “Yazd,” in the Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Ed., Vol. 11 (Brill: Leiden, 2002), pp 302-309. The best guidebook to Iran known to me is Nagel’s Encyclopedia-Guide Iran (Geneva: Nagel, 1968), but it is now rather dated. A contemporary one is M. T. Faramarzi, A Travel Guide to Iran (Tehran: Yassavoli, 2000). Robert Byron is quoted from The Road to Oxiana (London: Jonathan Cape, 1937), p 202. An earlier and truncated version of the present article appeared in the travel section of The New York Times in February 1971.